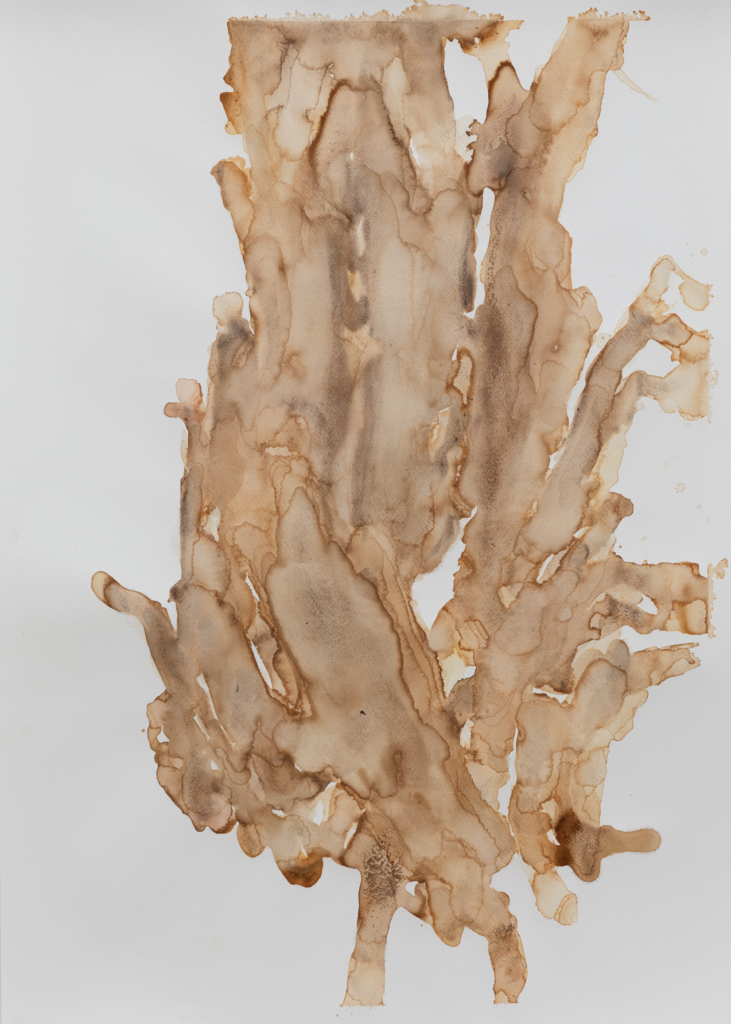

Mirroring 4, fungi pigment on paper 50 x 70 cm

Exhibition text

Ludvig Uhlbors

playwright, director

At one point, Hanna Sjöstrand discovered that she had developed a special relationship to trees. It happened during walks and stays in nature. She realized that there was a connection between her own experience of being in a body and the processes that take place inside trees. Investigating that experience through art made her aware of a question that has, on second thought, always been a recurring theme in her practice. How should one handle the issue of the original or model? Where does it occur? What is an original?

Trees have played a major role in art history, but usually with a focus on images of trees. These images represent trees in general, or rather greenery, and nature. Could Sjöstrand manage her experience of trees in a more comprehensive way?

It was through her work with face masks that a way appeared. A mask is placed as a surface in front of the face and it is there, in the space between man and mask, that the mask comes to life. The face is reflected in the adjacent surface, which becomes the outside, and what is behind the mask, the rest of the world, becomes inside.

Bark is the outside of the tree, its mask, which separates the within from the outside world. It falls from the tree, decomposes and becomes nourishment for the tree. It can then arise and return to being tree again. By picking bark and fusing it into masks, it becomespossible for Sjöstrand to position herself inside the experience of the tree; and at the same time turning the surrounding mask into a surface facing her, behind which the rest of the world may appear as trees.

It was here that she found the answer to the question of the original in relation to Of Trees. It was not the mere image of the tree, as it appeared before her eyes, that was the motif. Instead, the original became Sjöstrand’s intuitive experience of entering into her own likeness to trees.

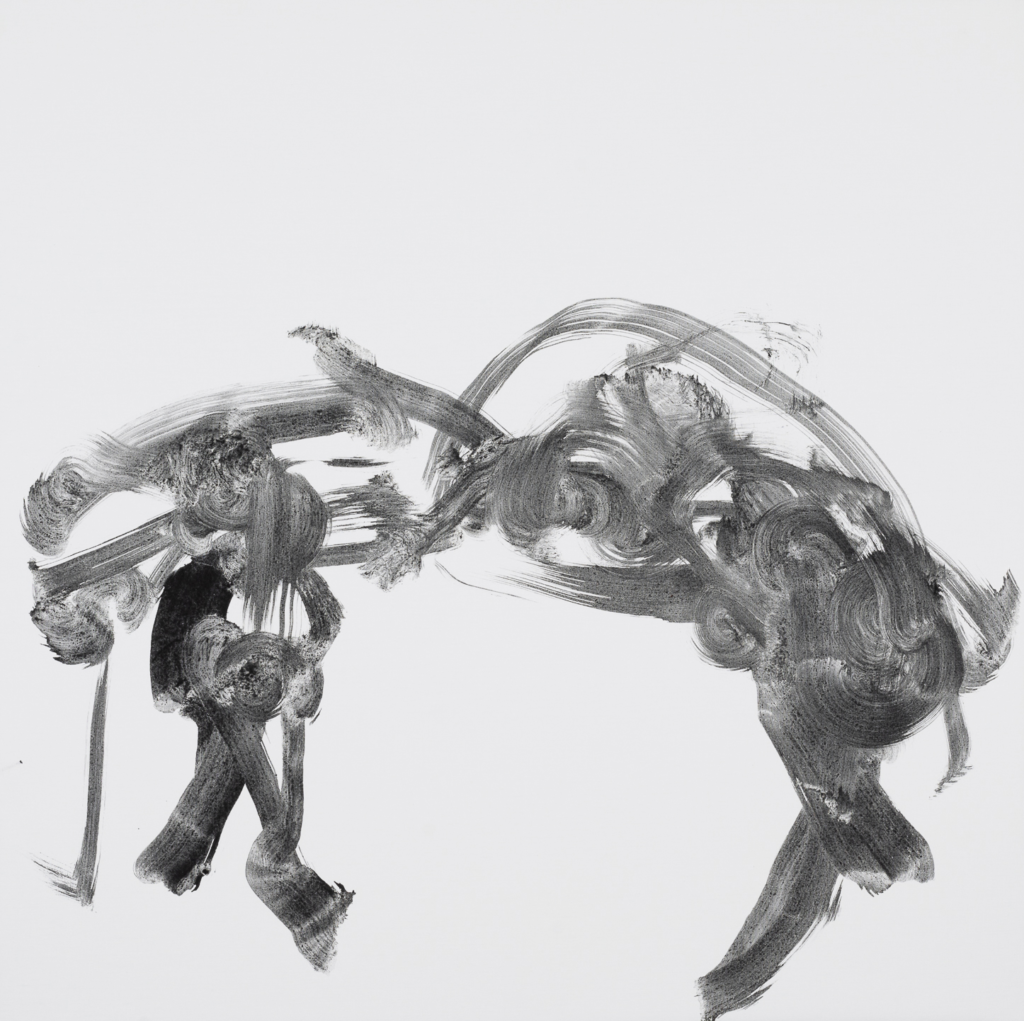

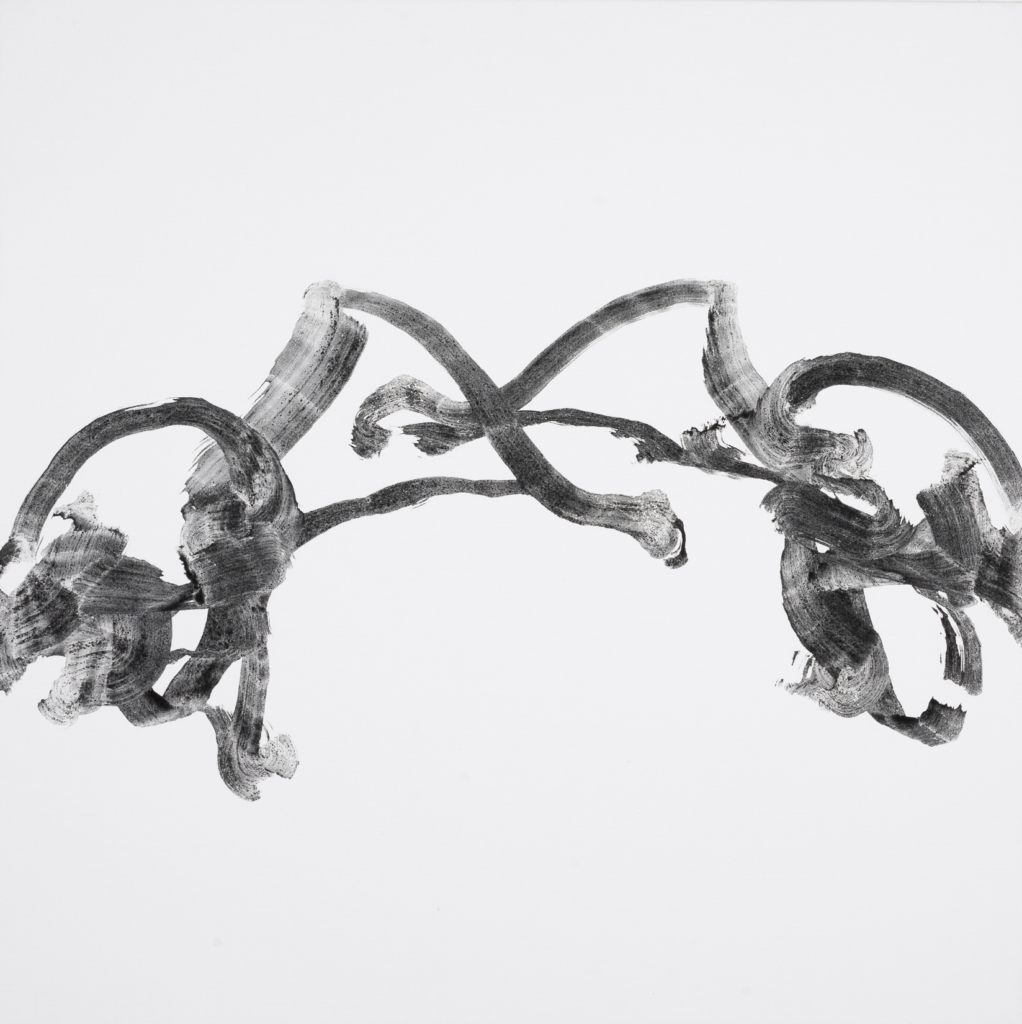

We recognize this from Sjöstrand’s other works. She enters different concepts to undergo transformations. The painterly gesture is an action that can relocate her, and that allows her to discover unknown topics.

Our relationship with trees is ancient. It goes so deep into our understanding of ourselves that laws have been written that forbid us to worship them. According to the drama theorist Eldredge, it is in the paleontological use of masks that we acquire an idea of ourselves. Many face masks from such cultures are inspired by our relationship to trees. The impulse to put something in front of one’s face is twofold. On one hand, it is an attempt to approach a material, but at the same time, that very action presupposes thinking of oneself as being separated from the object being held up. It is possibly here that theater, as well as dance, and other artistic impulses; including painting, is born.

The experience Sjöstrand is making in her work with Of Trees is that there is no distinction between what surrounds us and what is inside of us. Our lungs are filled with the air we breathe. The food we eat is a consumption of animals and plants, and is absorbed into our bodies and becomes a part of us. Painting is a language well suited to depict such an experience. It is, by all means, closely linked to the modernity that has alienated man from the earth, which often is both toxic draining of resources. But it is also something else. It is deeply rooted in time: all the way back to the old cave paintings, whose function was to train hunters in empathy.

Now that she approaches trees, Sjöstrand uses the same intuitivity. Her ambition places specific demands on the process and applied method. A mask practitioner should always design their own masks. It should be done with an intuitive understanding of the material and what shape it desires. In this case, it means that the masks are results of Sjöstrand’s understanding of the bark’s inherent will. At the same time, there is a predatory aspect inherent in Sjöstrand’s project. She takes bark, which is about to decompose and resurrect, and deprives it of the right to return to its natural flow. The bark stagnates, turns into a mask, and the flow is changed. This movement between compliance and one’s own desires is a prerequisite for creating a rewarding mask. It is only by establishing a personal practice, cultivated over a long period of time, that a mask wearer can build up the kind of sensitivity and responsiveness needed. The series Yielding is a clear result of such a discipline where Sjöstrand has explored those movements that can occur when a mask covers her face and creates impulses. The challenge is to be able to maintain compliance while pursuing a vision of achieving painterly expressions (visual marks on a canvas).

It is a well known phenomenon that a mask can merge with a wearer and that this can bring about something larger than both the mask and practitioner. This third appears as a kind of unknown being, not man or matter but something on its own. When this occurs, an observer will experience that the mask melts over the wearer’s face; that the muted surface becomes plastic, even alive. Mirroring has come about because of such a process. The paintings in this series are therefore not portraits of masks but rather something larger.

To produce one’s own pigment is a way of examining the pre-industrial artist’s experience of painting in a time before mass production and chemicals. Such artists could have direct experience of those processes which minerals and organic material went through. Participating in these transformations created a different approach to painting than the one common today. Sjöstrand has returned to their holistic experience by extracting pigments from mushrooms and ash. The choice of these particular materials brings her even closer to an understanding of trees.

Fungi detoxify trees, they transmit information between them and serve as a source of nourishment in times of malnutrition. The ash is taken from a 150-year-old maple tree that has grown in Sjöstrand’s garden.

Of Trees, Galleri Thomas Wallner 2020

Foto:Andreas Larsson