Brushes in the exhibition WORK at Galleri Thomas Wallner

Balzac’s short story The Unknown Masterpiece has resonated throughout the history of modern art up to the present. In spite of the novella’s title the masterpiece does however not simply remain unknown in the sense that it may be discovered at some later point, but it is just as unknowable for its audience as it is impossible for its maker to produce: it is a work that signals nothing but its own dissolution, which is probably why it still retains the quality of a seductive enigma. In the character Frenhofer, whose failure to achieve a masterpiece unaided by the inherited systems of rule leads him to destroy the work as well as to take his own life, the problems of modern art are as it were condensed into a single figure, and he would become a constant reference for artists from Zola to Cézanne, Rilke, and beyond, positive as well as negative.

The novella on one level unfolds as a drama with three male artist protagonists, Frenhofer, Porbus, and Poussin, on another between the three men and two women, who also provide the names for the novella’s two chapters: Gillette, Poussin’s mistress who eventually sacrifices her honor and poses for Frenhofer, which then gives Poussin access to the other and imaginary woman, Catherine Lescault, La belle noiseuse, who withdraws from sight and in Frenhofer’s destroyed masterpiece only leaves her foot as a trace of an impossible presence, the pursuit of which has led Frenhofer to ruin and death.

The three men stage a battle between the excesses of genius and the balance of le juste milieu, the first displayed in Frenhofer’s quest for the abyssal depth of color, the second in Porbus’s demand for moderation through drawing, between which the young Poussin has to find his own path. Rather than Frenhofer’s dream of reuniting with nature, where everything is a plenitude without gaps, Porbus stresses the limits of art, and that one must never “philosophize” without holding the brush in one’s hand, i.e. never attempt to transgress the rules of art. To follow in Frenhofer’s footsteps would be disastrous, he cautions the young Poussin, since it dissolves the link uniting thinking and sensibility, thought, hand, and eye, which tempers the work and ascertains that it may reach a definite end, and instead it opens a limitless descent into the sensible that produces a confusion of faculties beyond repair, a “chaos of color, half-tints and vague shadows that made up a dim, formless fog.”

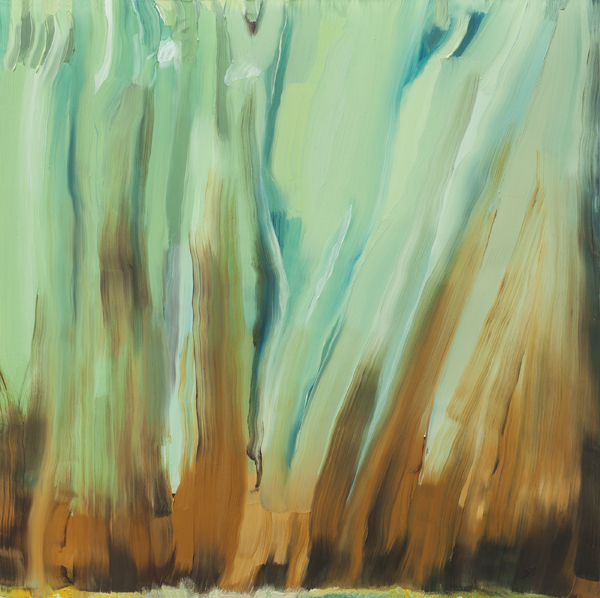

Hanna Sjöstrand’s exhibition WORK approaches this legacy through a set of moves that bring out the complex legacy of Balzac’s story. Continuing the interrogation in her earlier works of the role of the romantic painter, she here draws out from Porbus’s emphatic claim about the link between the hand and the canvas, and in the series Brushes folds it back onto itself by rendering the tool itself in painting, and then repeating the process in several steps, including photographic representations that in turn are transferred back into painting. The instrument that was to underwrite the stability of form is itself multiplied, deferred, and made into a fluid material.

The second section, showing five works entitled Painted, takes its cues from Paul McCarthy’s irreverent film The Painter (1995), which presents us with a scatological parody of the phallic expressionist painter splashing paint onto his canvases—Frenhofer as it were transplanted to California. Here too Hanna Sjöstrand introduces an element of slowing down and repetition, in using the splashes that result from the protagonists painterly ejaculations as motifs, and reproducing his movements in order to produce new form, which itself might be another result of McCarthy’s procedure, just as unintended as inevitable.

Rather than a critique of the legacy of abstract expressionism, or a meta-critique of the today equally canonized dismantling of its pretensions, Hanna Sjöstrand explores the interstices of this exchange, a third element that neither affirms nor rejects, but draws on the possibility of extracting something new out of gestures as well as counter-gestures that for a long time have seem embalmed and consigned to history.

Sven-Olov Wallenstein

Foto: Lotten Pålsson